Death of an Exile

- Apr 19, 2018

- 8 min read

Updated: Apr 19, 2024

public domain

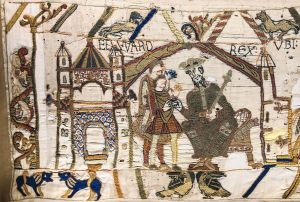

Edmund Ironside died in November of 1016. He was known as the _Ironside_ for his strength and prowess in battle. There is mystery surrounding his death. Some say that he was murdered – something nasty involving the call of nature and a spear from the rear – but the general consensus seems to be that he died of his wounds three weeks or so after the Battle of Ashingdon ( Assundun in Old English). The agreement he’d made with Cnut following the battle was that the Dane should rule the North of England, and Edmund the lands in the south and south-west – Wessex. Included in the agreement, was this clause: whomever died first, the other would take over their crown. The next year, whilst he was on a housecleaning excersize (getting rid of anyone who’s loyalty to him he believed questionable) it occurred to Cnut that Edmund’s infant sons, Edward and Edmund, would grow to become a real threat to his rule. He asked his wife what she thought about the boys and she urged him that he could not allow them to live. So he had them banished – snatched, apparently, by the treacherous Eadric Streona, from their mother’s arms. They were sent to Sweden with a message that they should be put to death. But the King of Sweden was not having any of it, infanticide wasn’t his thing, and so he let them go. This led to the boys embarking on a long journey through Eastern Europe, ‘on the run’ so-to-speak, until they settled eventually in Hungary at the court of King Stephen.

At this point, I am not sure what happened to Ironside’s son Edmund, but he doesn’t seem to have been alive when Bishop Ealdred is sent to seek out his brother Edward. However, it comes to the attention of the Confessor that Edward Ætheling, his brother’s son, is alive and well and living in state at the court of Hungary, married to a European noble lady and with a ready-made royal House of Wessex family. This came about when discussing a succession plan in a meeting with the Witan in May 1054, that did not include William of Normandy. King Edwardof England and his wife, Edith, had failed to produce an heir for the English throne, and it must have looked unlikely by now, as they had been married for 9 years, that it would happen any day soon. There were few other candidates apart from this lost exile living in Hungary, but these men, Ralph and Walter de Mantes, might have been in the running as Edward’s sister’s (Goda) sons; Ralph would later turn out to be incompetent, and Walter later dies at the hands of William, imprisoned in 1061. But seeing as they were not sons of a king, it obviously seemed the rational thing, to send a mission to Hungary to find King Edmund’s son.

Edward, it seemed, caused himself much grace and favour at the Hungarian court, and lived under five kings during his life there. When he eventually returns to England, he is sent home with an entourage of servants and much gold and treasures to support his family, so he must have been well regarded and treated and possibly a particular favourite of King Andrew. King Stephen I died in 1038 without any issue to take his throne, his nephew, Peter Orseleo, son of the Doge of Venice, promised to protect the people of Hungary and Stephen’s wife and took the throne with the support of the dowager queen’s German faction and terrorised the Hungarian people, and started senseless wars abroad (Ronay 1989). An uprising got rid of him in 1041, but he was restored in 1044 with the help of Henry III, Holy Roman Emperor. In thanks for the emperor’s assistance, he accepted Henry’s overlordship. With Peter restored, the Hungarians were not happy to live under his rule, and were most likely also unhappy with the Holy Roman Emperor’s interference. They decided they needed a hero, and suddenly remembered one who had been living in exile in Bohemia for 15 years, Andrew who was descended from the Árpád dynasty, offspring of Stephen’s dynasty. It was when the envoys came to Kiev, where the English exiles were at this time said to be living, in 1045, they decided to join Andrew’s crusade to help free Hungary from the tyrannical rule of Peter (Ronay 1989).* And so when the Confessor agreed to send a delegation from England to Europe to help find his long lost nephew, they must have already heard that Edward son of Edmund Ironside, was living in Hungary.

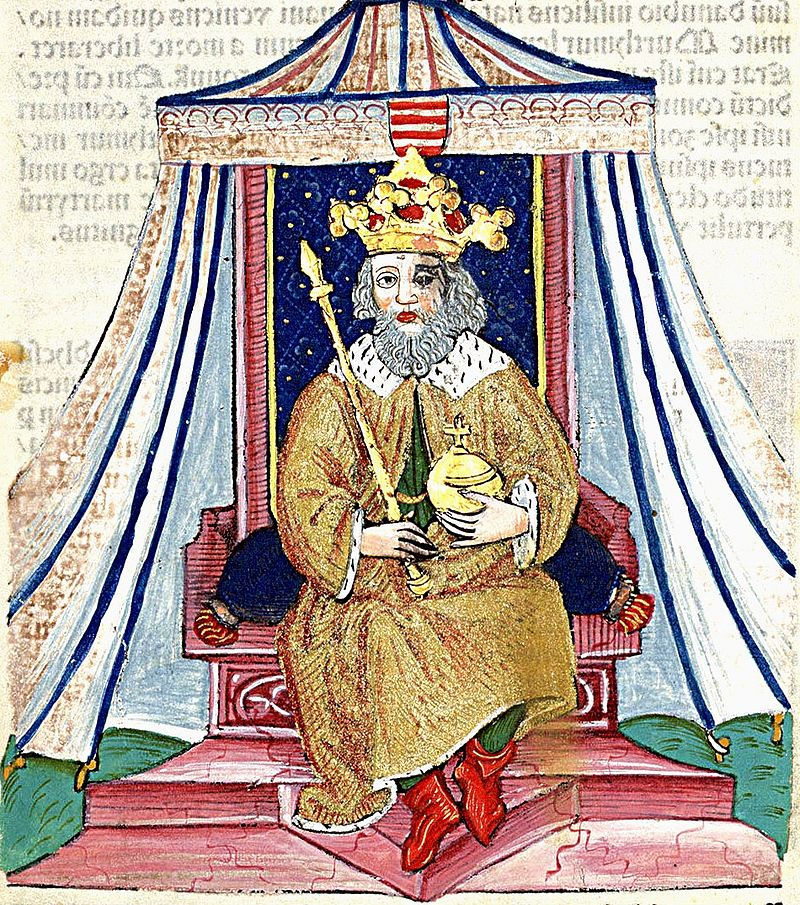

Peter of Hungary

Ealdred, Bishop of Worcester and his companion Abbot Ælfwin of Ramsey, set off abroad in 1054, and travelled to the court of Henry III, the Holy Roman Emperor in Cologne to request that the Emperor liaise on King Edward’s behalf for the return of his kinsman to England. Why did Ealdred’s embassy go to Germany and not direct Hungary I am not sure. It could be that perhaps historically, England had closer ties with Germany than Hungary. The Confessor’s half sister, Gunnhilda had been married to Emperor Henry III, but had died almost 20 years since. Or perhaps it was because Agatha, Edward the Exile’s wife, was a niece of the emperor. In any case, Ealdred sought Henry’s help but although Ealdred was invited whilst the emperor made the necessary inquiries, to study the German church, and Ealdred, perhaps being unusually naive, as suggested by Ronay, was in complete oblivion about the strained relations between Germany and Hungary, the mission was not successful. Given the past hostile history between the two territories, it seems strange that Ealdred should have failed to realise the situation was sensitive. Emma Mason, in her book The House of Godwine states that Henry was unable, or unwilling to help the situation, indicating that Henry might have had his own agenda in his reluctance to find the exiled aetheling. It seems that Edward arrived in Hungary with the army of Henry’s enemy, Andrew I, and even though Edward had married Henry’s niece, Agatha, Edward’s involvement in the wars against German-backed Peter Orseleo, had displeased Henry enough to try and sabotage the aetheling’s ascension to the throne of England.

So, as the Anglo Saxon mentions, in 1055, about a year later, Ealdred returns to England with much knowledge of how the German church worked, bringing gifts with him from Archbishop Hermann II a copy of the Pontificale Romano-Germanicum, and a set of liturgies, with him, but no future heir to the English throne, just an empty promise that Henry would do what he could to find the missing English heir.

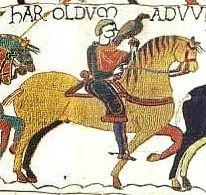

This obviously wasn’t good enough and the Confessor must have felt disappointed at the failed mission. Someone within the court might have had more knowledge of why the mission failed and suggested that someone more assertive and less distracted by churchly wonders be commissioned to negotiate the return of the Exile. Whatever the case, Harold Godwinson was dispatched to St. Omer in the autumn of 1056 and eventually brought Edward, son of Edmund Ironside, the only lone male with a direct link to the royal Wessex line, and his family, home.

The fact that Harold’s delegation to collect Edward Ætheling home was successful, could have had something to do with the death of Henry III around the time of Harold’s embarkation. And so perhaps dying with him, his resentment at the Hungarian regime. Whatever the case, negotiations were successful. There does not appear to be any source that directly quotes that Harold was the man who brought the Exile home. However most historians accept that because there is evidence that Harold was abroad at this time, travelling to Rome and witnessing documents in St. Omer, it was he who brought Edward back to England.

We might think of this mission as bringing Edward ‘home’ but in actual fact, it was not his home, but rather his place of birth. He was at least 40 years old, and had lived abroad for nearly all of his life. He would not have recognised London the day he set foot in it. He might have stayed with Harold at one of his manors, with his family: wife, Agatha, daughters Cristina and Margaret who was later to become one of Scotland’s favourite queens, and his little son, Edgar. He must have arrived to much cheering and waving and glad tidings, but why the Confessor was not there to greet him, it is not known. It must have been a strange feeling to him, to be in the land that had allowed that treacherous Cnut to send him away with a letter of death, to deny them him his birthright and his home. Had Edward longed for restoration to his rightful place in society? Had he asked, requested, suggested, and begged for an army to support his right to the throne and it been denied? Had he just accepted his lot, and then one day, like had happened to the Confessor, he was called home, to his great surprise, eagerness, or reluctance perhaps? It is difficult to know. And it became unlikely that anyone would have got to know his thoughts, but the man who brought him home, and we have no record of their interactions, just like there is little evidence for anyone else from that time. In any case, Edward the Exile was not long for this world when he stepped off the boat and onto England’s shores on the 17th of April, for he was dead within 2-3 days.

The chronicles do not record how he died, but there is a hint of dastardly doings. The Worcester Chronicle states:

We do not know for what cause it was arranged that he might not see his relative King Edward’s face, Alas that was a cruel fate, and so harmful to this nation that he so quickly ended his life after he came to England…

So, was there foul play that befell the ætheling? Ronay, in his book about Edward’s life purports the argument that Harold Godwinson poisoned him. He states that he was closest in proximity to him and had the most to gain. It is food for thought, however I do not think that Harold was thinking that far ahead. This was nine years before the Battle of Hastings, and eight years before his trip to Normandy. I also think that had Harold decided to get him out of the way, he probably wouldn’t have done it as soon as they stepped on English soil. He was not a stupid man. I can imagine the whisperings that the ætheling’s sad demise must have caused, but as far as I know at this point in time, the accusation was never actually levelled directly at Harold in any of the contemporary sources or even later ones, though I have yet to do an exhaustive, thorough investigation.

Harold Bayeux Tapestry

Could William of Normandy been involved? I would love to say yes, but I think not. At this time, he was just recovering from keeping his dukedom in check. Would he have wanted the Exile out of the way? Yes, definitely. And enemies had been known to die in his custody, such as Walter de Mantes, another possible heir to the English throne, albeit a bit of an outsider. But again, I do not think he would have had the wherewithal to have killed Edward. Unless perhaps a Norman supporter on the other side of the channel.

All i can say is that it is a shame that the chroniclers of the time couldn’t have been more explicit in their writings. It would have been good to have so much more detail, however this is all that we have to go on, and only two of the Anglo Saxon 6 chroniclers mention Edward’s death at all.

So what happened next? His family were taken into the care of the king’s household. His queen, Edith would have looked after Agatha and her children, possibly overseeing their education and welfare. Not long after his father’s death, Edgar was to be endowed with the appellation of ætheling, indicating that he was accepted by the Witan as the nominated heir. The sad tragedy of Edward’s untimely death must have weighed heavily on most people’s hearts, none more, probably, than the king’s, however Edward’s need to divert the problem away from Normandy, and as some have implied, the growing power of the Godwinsons, had been accomplished. The succession was sown up (Walker). Edgar was England’s great hope for the future.

*For what the ætheling’s were doing in Kiev at this time see The Lost King of England by Gabriel Ronay.

References

Mason E. 2004 The House of Godwine (1st ed) Continnuum

Ronay G. 1989 The Lost King of England Bydell Press, UK

Walker I. 2010 Harold Godwinson: The Last Anglo Saxon King The History Press; New Ed edition

Comments